Before the invention of screws, when nails were around but too expensive for common use, most wooden structures, like door frames, cabinets, and chests, were put together using intricate joinery. These techniques are still used today although the joints are often cut with power tools like routers rather than the hand tools they used to use.

We’re going to take you through the various types of wood joints and compare them against one another. While there is a lot to know about wood joints, you’ll leave here today with a much better idea of wood joints and their uses. Let’s get started.

Why Use Joinery?

With the modern availability and decreasing price of screws and electric drills, you might wonder why intricate joinery is still being used. In many cases, it’s not. Flat-pack furniture like you’d buy at Ikea uses butt joints, the simplest type of joinery, held together by nails, screws, and other mechanical fasteners, which works well enough for that purpose. However, this furniture is often made of particle board that will crumble or fall apart with older joinery techniques.

For furniture and structures made of solid wood that are intended to last a long time, the more traditional types of joinery help to make the joints stronger and sturdier. For the most part, this is done by increasing the surface area available to be glued, but in some cases, the joinery also has a mechanical strengthening purpose.

For example, dovetails are often used to create drawers. The angled nature of the dovetails prevents the front of the drawer from being pulled apart from the rest of the drawer structure despite the force applied when opening the drawer.

Joinery Categories

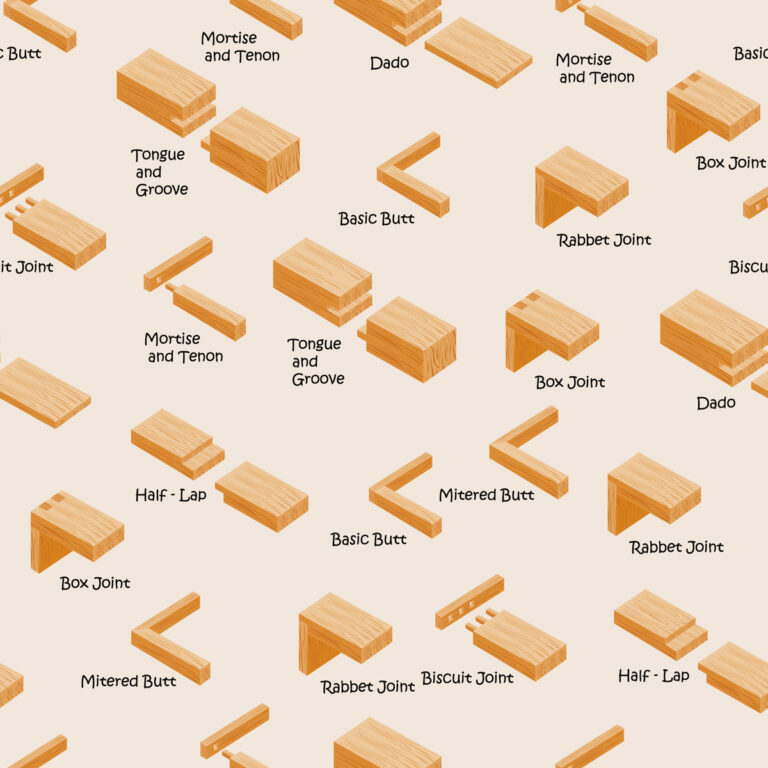

- While there are countless types of joints, they typically fall into one of three categories:

Box or corner joints are used to connect the ends of two boards to create an angle (normally 90 degrees) like the corner of a drawer or box. - Framing joints are used to connect the end of one board to the center of another. They are commonly used when making the frame of a structure like cabinets, bookshelves, or chairs.

- Widening joints are used to connect to boards side-by-side or end-to-end to make a longer or wider board. They are often seen in tabletops and large surfaces like hardwood floors.

Many of these joints can be used in other categories or combined with another type of joint to make a new joint. For example, a half-lap joint can be combined with a miter joint (unsurprisingly called a half-lap miter joint) to make a stronger corner joint.

Boxed In: Box/Corner Joints

As described previously, box or corner joints are used to connect two ends to create an angle, like the corner of a drawer or picture frame. Like these two examples, the boards or pieces of wood being joined might be wide/narrow or thick/thin, but they are almost always the same width and thickness as each other. If they are too different it becomes much more complicated to join them together.

There are many joints in this category but there are three main types that are commonly used as corner joints.

Butt Joint

This is the most basic wood joint, with two ends put together at a 90-degree angle and secured using nails, screws, or other fasteners. Glue can be used to further strengthen the joint but should not be used alone. Butt joints are also used as framing joints and widening/lengthening joints, sometimes in combination with other joints like a half-lap

Miter Joint

This joint is most likely to be seen in picture frames and decorative moulding. The two ends are cut at a 45-degree angle and stuck together to create a 90-degree angle (as seen in the image below). The ends are fastened with glue, and if more strength is needed, reinforced with nails, staples, splines, or other fasteners.

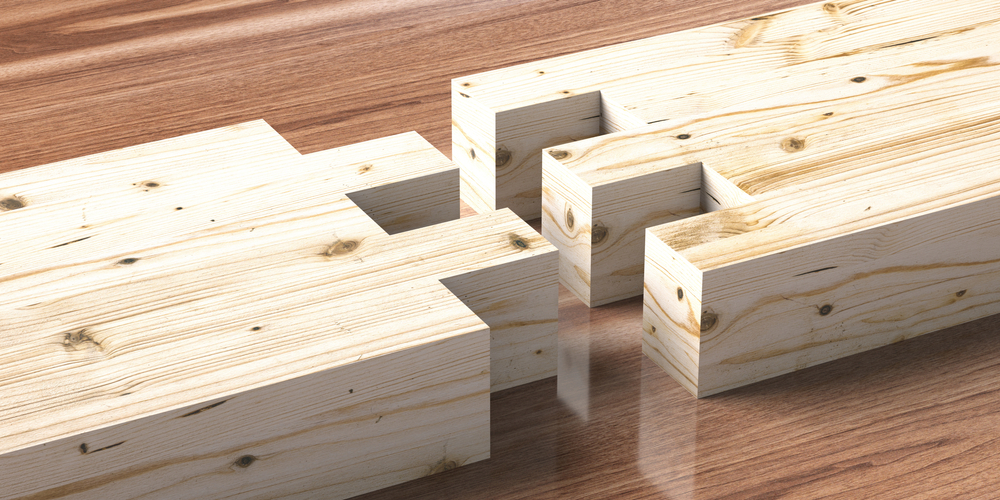

Dovetail and Box Joints

These joints are slightly different but fulfill a similar purpose. The increased surface area of these joints makes them very strong even if only glue is used. Other fasteners can be used but they are generally not necessary.

Dovetail joints are slightly splayed and mechanically strengthen the joint in the direction where force is normally applied, this makes them a favorite option for joining boards for drawers. They can be tricky to cut, and many opt to cut them using a router. It is a good show of skill if a woodworker can cut dovetails by hand.

Box joints look similar to dovetails but have straight edges rather than a fan shape. They are much easier to cut but don’t have the same mechanical strength as dovetails.

In the Frame: Framing Joints

Framing joints are used to connect the end of one board to the middle of another board or to join the middle of two boards. You’ll see this type of joinery in cabinets, bookshelves, and other structures, like chairs. As with corner joints, some framing joints are simpler than others and might require fasteners to help strengthen them.

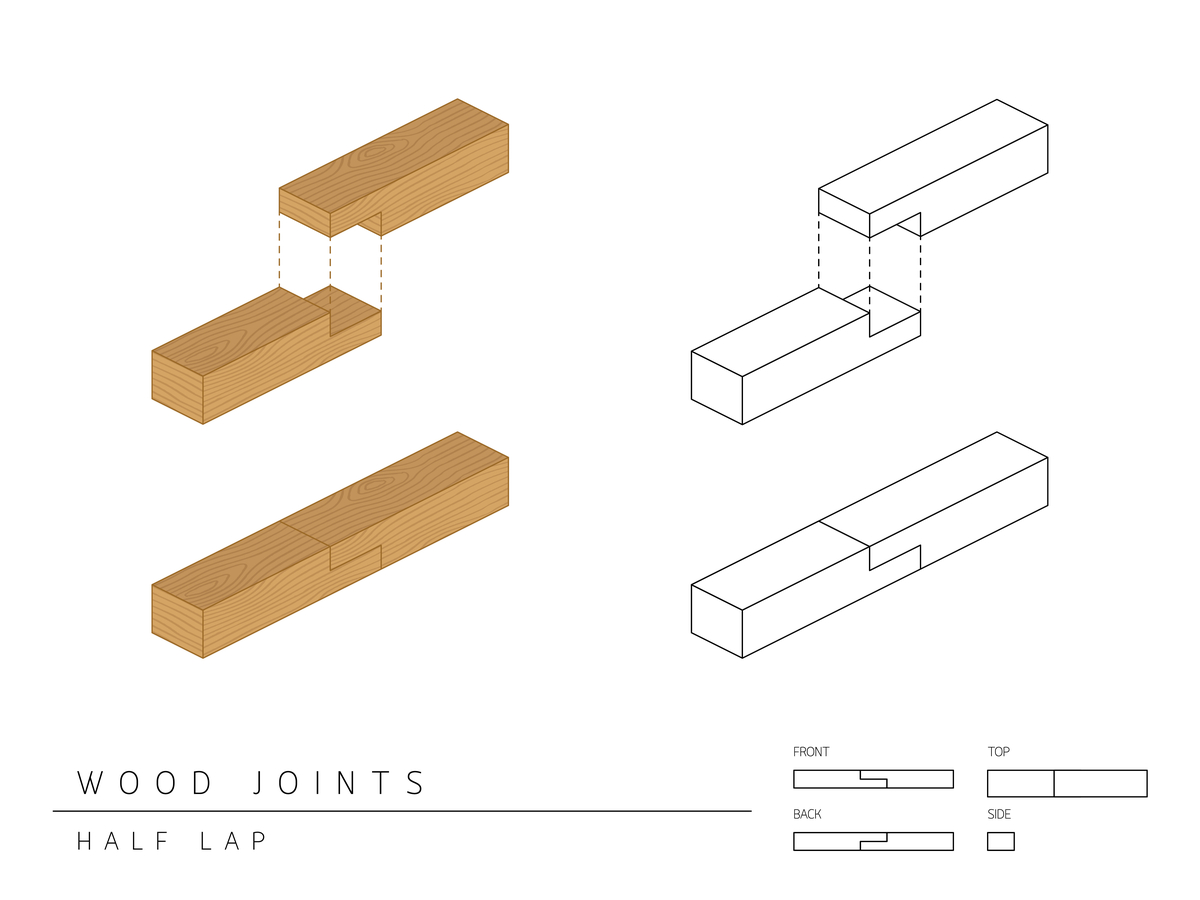

Half-Lap Joint

In this joint, each board has a block cut out of it to roughly half the depth of the board. This allows the two boards to be placed together, usually at 90 degrees to each other. Because of the part that has been cut out of each one, the boards are flush with each other, creating a strong but flat structure. Half-lap joints can be used at any point where two boards come together, a corner, a T-joint, or in the middle of two boards that cross over each other.

Half-laps are often combined with other joints, like miter joints and dovetails, for the dual purpose of increasing the surface area for glue and neatening the appearance of the joint.

Mortise and Tenon

You’ll most commonly see this joint in structures like chairs where there is a horizontal piece of wood between two upright boards. The end of one board or piece of wood is cut smaller and fitted into a hole cut into the other piece of wood. In the example of our chair, often the same joint is repeated on the other side of the horizontal piece of wood.

This creates a sturdy joint that won’t slip out of place.

Mortise and tenon joints are usually strong enough with only glue but can be further strengthened with a dowel or through tenon.

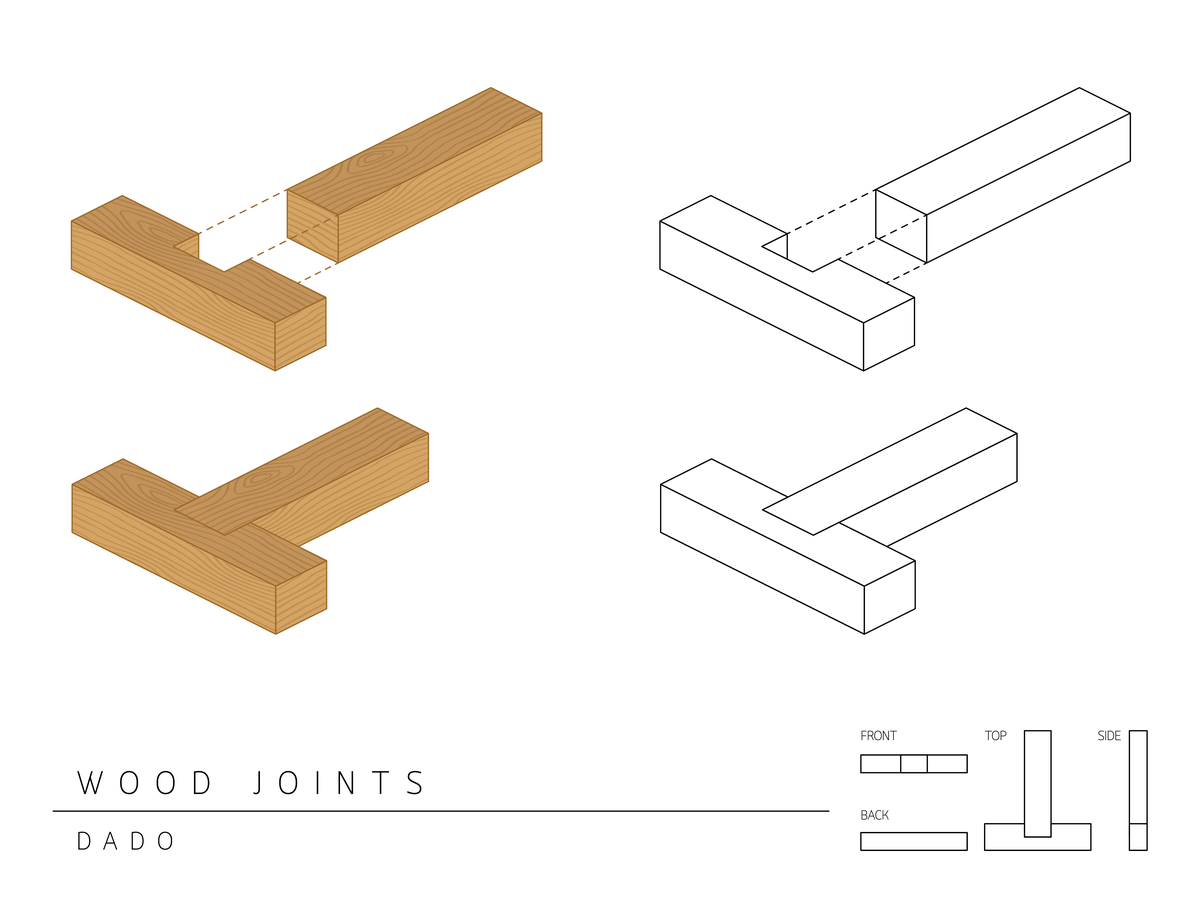

Dado

Dado joints are like mortise and tenon joints in that they are often used to insert the end of one board into the middle of another. However, while mortise and tenons are mostly used on narrower pieces of wood, like for chair backs, dado joints make it simpler to connect wider boards, like the shelves in a bookcase. Instead of cutting the end of one board smaller, the board is kept as it is and the groove in the other board is cut to accommodate it.

Coupled Up: Widening/Lengthening Joints

The joints in this category are mostly used to create large wooden surfaces out of several boards. For the most part, they are used to make wide surfaces like tabletops and wooden floors, but they can also be used to make boards longer, often used in tall structures.

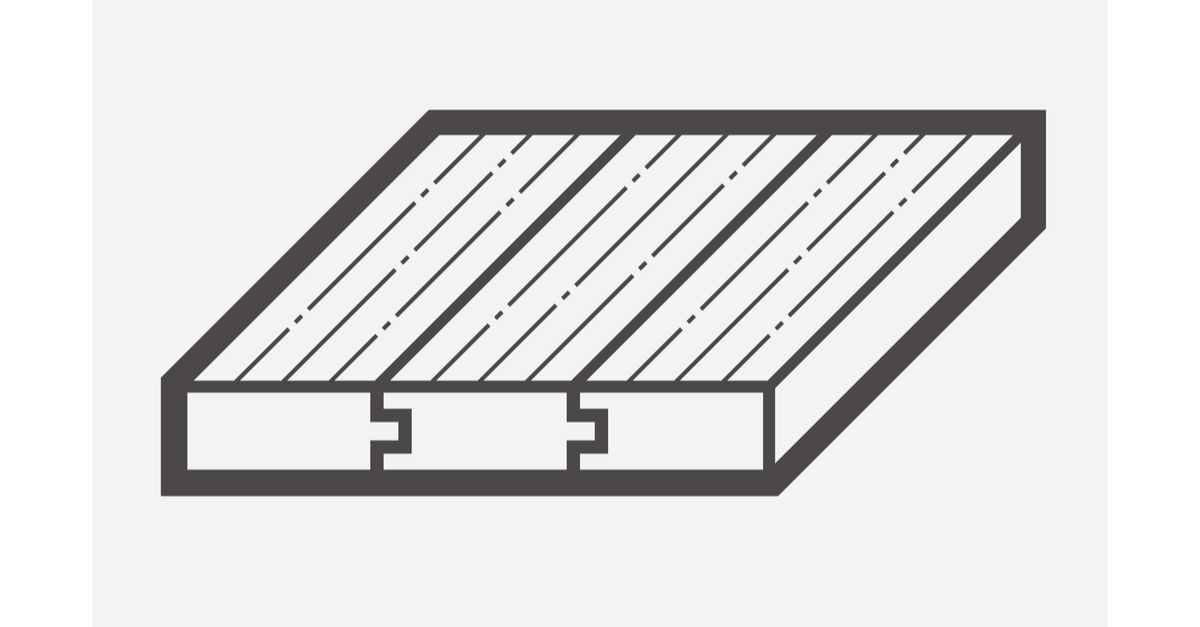

Tongue and Groove

Tongue and groove joints are primarily used to create wide wooden surfaces. It consists of a long groove along the edge of one board, and a matching tongue or protrusion on the facing edge of the adjacent board. They fit together like jigsaw puzzle pieces. Hardwood floors use this joint a lot but usually come pre-cut.

You probably won’t need to cut this joint yourself unless you are building your own tabletop, and even then, you might prefer to use a butt joint, dowels, or another type of mechanical fasteners to join your boards. The benefit of a tongue and groove joint is that it keeps the boards aligned to each other.

Finger Joints

You are unlikely to create this joint yourself as a woodworker, but you will probably come across it often when buying lumber. Manufacturers often use finger joints to create long boards and pieces of wood that can then be cut to your desired length for a project. Finger joints tend to be very strong and difficult to cut through.

Fasteners

Although joints usually fit tightly, they are often further secured using glue, nails, screws, or other fasteners like dowels or biscuits. You are most likely familiar with nails and screws so we won’t go into detail about them other than to say they can be used to strengthen almost any joint described here although they are usually not necessary with the stronger joints like dovetails and mortise and tenons.

Dowels

Dowels are an interesting type of fastener as they can be used in a variety of ways. they can be a visible fastener running through the entire joint like a nail or screw, as shown in the image below.

Alternatively, they can be hidden, strengthening the joint from inside as in the image below. This use makes the dowels function similarly to a mortise and tenon joint but is often much easier to use when joining two long or wide boards.

Biscuits and Splines

Splines and biscuits (not the kind you eat) are small pieces of wood used to internally strengthen a joint, like hidden dowels. A small notch is cut into each board that is to be joined together, then a biscuit or spline is glued into the notch in one board and fits snugly into the matching notch of the facing board. You’ll often find splines in miter joints. Biscuits are used in joints like butt joints where a hidden dowel could also be used.

Join the Club

There are a great many types of joints not described in this article but many of them are combinations of the joints included here. If you have a particular project in mind, it is useful to research how others have done similar types of projects to see which types of joint they used.

As explained here, some joints are better for certain purposes than other joints, but the primary function of all of them is to connect two (or more) pieces of wood in such a way that they will not easily fall apart. If you are just starting your woodworking journey, welcome to the joinery club!